March 16, 2023|כ"ג אדר ה' אלפים תשפ"ג Say His or Her Name

Print Article

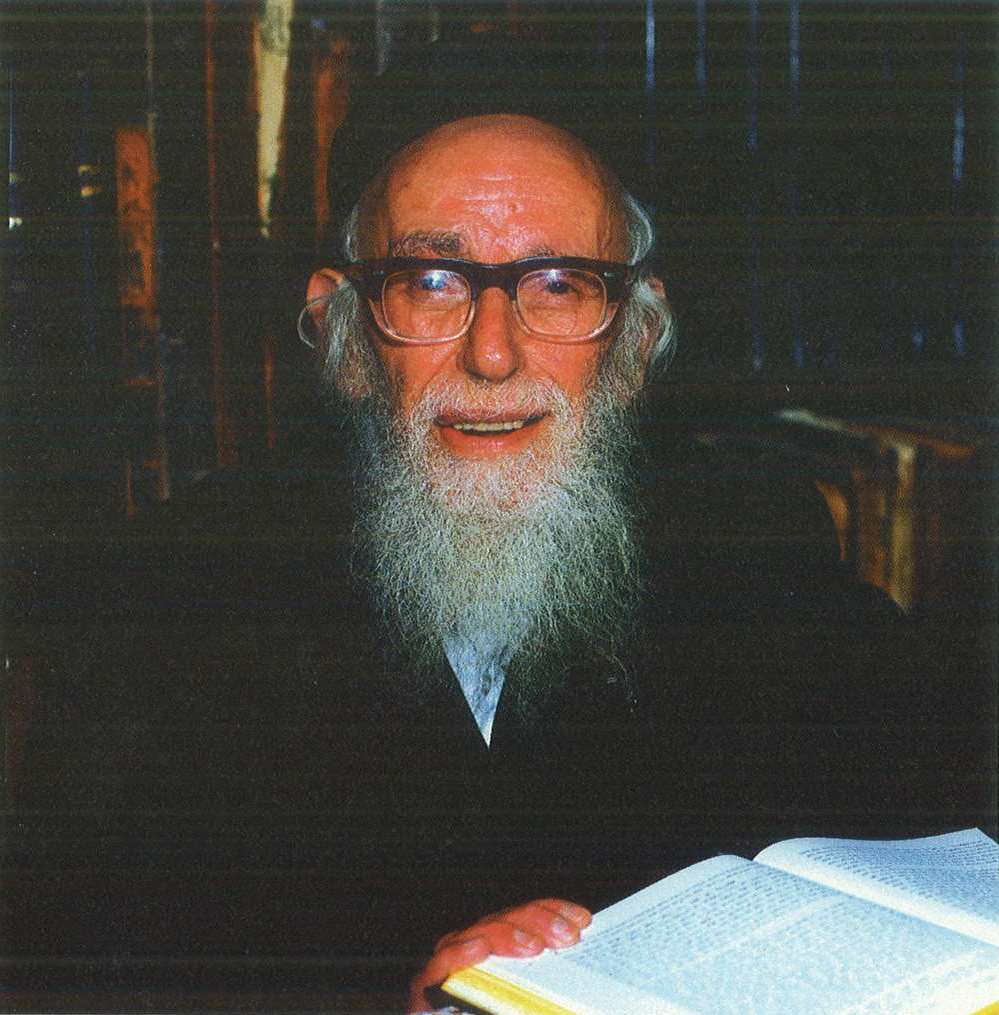

Earlier this week, the 20th of Adar, marked the yahrzeit of the great Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach zt”l. In a tribute written shortly after his passing, Rav Aharon Lichtenstein, who shared a very close relationship with Rav Shlomo Zalman, described him as a “Gentle giant.” He wrote:

Reb Shlomo Zalman was endowed, as a lamdan, with a set of qualities which served him, ideally, as a posek. He had encyclopedic knowledge — and he had it, as mechudaddim beficha, at his fingertips. His temperament was remarkably judicious, invariably level-headed, and never pedestrian. He was deferential to the views of others, and yet genuinely self-confident. He could be innovative and even daring.

Rav Shlomo Zalman’s brilliance was undeniable, and yet it was perhaps surpassed only by his humility and sensitivity to all. R’ Chanoch Teller recounts the following anecdote: “When Rav Shlomo Zalman passed away, a beggar in Sha’arei Chesed sobbed in her anguish: “Now who will say ‘good morning’ to me every day?” (Mi yagid li boker tov?)”

While a testament to his unpretentiousness and accessibility, the anecdote has the potential to leave the reader believing that one must be the gadol ha’dor, the greatest of the generation, to be friendly, caring and gracious to all. Indeed, Rav Shlomo Zalman’s greatness was seeing his warmth and friendliness as nothing extraordinary at all, but something that should come naturally and be instinctive.

The Talmud testifies (Berachos 17a) about Rabban Yochanan ben Zakai that no one ever preceded him in a greeting [of Shalom], even a stranger in the marketplace.” The Mishna in Pirkei Avos (4:20) encourages us all, "Hevei makdim b'shalom kol Adam, be the first to greet each person." The Maharal explains that when you walk by someone without offering a greeting you make him or her feel invisible and insignificant. By making a point of greeting someone you demonstrate that you don’t see yourself as superior or better than another. Rather, by instigating the greeting, you show that you respect that person as an individual and thereby you give them dignity and worth.

In his book, “Reflections of the Maggid," Rabbi Paysach Krohn tells the following story:

In Argentina there was a ritual slaughter complex, comprised of several buildings. There was a building where the animals were fed, a building where they were slaughtered and the meat packed and loaded onto trucks, and an office building with dressing rooms for the shochtim (ritual slaughterers). The entire area was surrounded by a tall chain link fence and everyone entered through a wrought iron gate in the front, near the parking lot.

The owner, Yisrael (Izzy) Nachmal, was a workaholic. He was the first one in every morning and the last one out every evening. He oversaw every aspect of his company, Ultimate Meats, and made it a point to know every worker. The guard at the front gate, Domingo, knew that when Izzy left in the evening, he could lock the gate and go home.

One evening as Izzy was leaving, he called out to the guard, "Good night, Domingo, you can lock up and go." "No," Domingo called back, "not everyone has left yet." "What are you talking about," Izzy said, "everyone left two hours ago!" "It is not so," Domingo said, "One of the shochtim, Rabbi Berkowitz, hasn't left yet." "But he goes home every day with the other shochtim, maybe you just didn't see him," Izzy said. "Believe me, I am positive he didn't leave yet," the guard insisted. "We better go look for him."

Izzy knew that Domingo was reliable and conscientious. He decided not to argue, but instead got out of his car and rushed back to the office building with Domingo. They searched the dressing room thinking that perhaps Rabbi Berkowitz had fainted and was debilitated. He wasn't there.

They ran to where the animals were slaughtered, but he wasn't there either. They searched the truck dock, the packing house, going from room to room. Finally they came to the huge walk-in refrigeration room where the large slabs of meat were kept frozen.

They opened the door and to their shock and horror they saw Rabbi Berkowitz rolling on the floor, trying desperately to keep himself warm. They ran over to him, lifted him off the floor and helped him out of the refrigerated room, past the thick heavy wooden door that had locked behind him. They wrapped blankets around him and made sure he was warm and comfortable.

Izzy Nachmal was incredulous. "Domingo," he asked, "how did you know Rabbi Berkowitz hadn't left? There are over two hundred workers here every day. Don't tell me you know the comings and goings of every one of them?"

The guard's answer is worth remembering. "Every morning when that rabbi comes in, he greets me and says hello. He makes me feel like a person. And every single night when he leaves he tells me, 'Have a pleasant evening.' He never misses a night - and to tell you the truth, I wait for his kind words. Dozens and dozens of workers pass me every day - morning and night, and they don't say a word to me. To them I am a nothing. To him, I am a somebody. "I knew he came in this morning and I was sure he hadn't left yet, because I was waiting for his friendly good-bye for the evening!"

When you are checking out of a store, make it a point to look at the person’s nametag and use his or her name. Instead of feeling invisible or anonymous, you will give them a sense of identity and dignity. We may not have encyclopedic Torah knowledge, but every one of us can be extraordinary just by making a point of greeting everyone with a smile.