January 9, 2015|י"ח טבת ה' אלפים תשע"ה Korbanos (Sacrifices) are More Relevant Than Ever and We Should Pray for their Return

Print Article

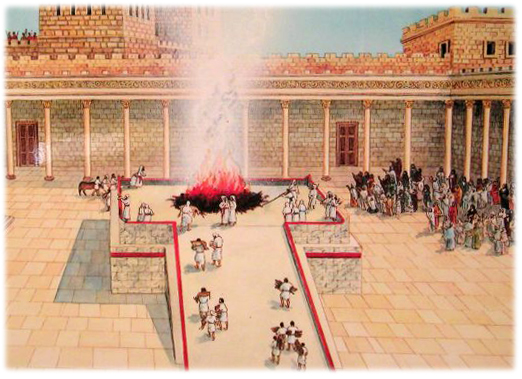

In a recent, highly controversial blog post, “Please G-d, Help me to understand why we must pray for a Third Temple!” the author offers arguments in the form of a prayer to God against the reinstatement of animal sacrifices and bluntly asks, “Is the rebuilding of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem what is best for us?” As a basis for his position and plea, the rabbi contends that both the Rambam and Rav Kook believed that the third Temple will not include korbanos (animal sacrifices).

In his usual scholarly and compelling fashion, Rabbi Dr. Ari Zivotofsky already rebuffed such an assertion in a compelling and conclusive way. He concludes his article by saying, “So will there be sacrifices in the Third Temple? The overwhelming majority opinion is that there will be. Rambam and Rav Kook seem to share this view.”

Many responses to the blog post correctly point out how absurd such a personal “prayer” is, given the centrality of longing for the third Temple in general, and pining for the return of sacrifices in particular, are to our liturgy, observances, and Jewish consciousness. They bring countless sources from Tanach, our siddur, and ma’amarei chazal (statements of our sages) that see redemption and the eschatological era as synonymous with the building of a third Temple and the return of the system of sacrifices.

Rather than seek to contribute to the conversation from the perspective of scholarship or theology, I would like to offer a thought from the perspective of symbolism and meaning. The author of the controversial post argues, in the form of a letter to God:

While livestock was once our primary resource and a meaningful sacrifice, today Your world operates in a different model of commerce. We would have new and more powerful contributions to sacrifice. Your people must be a light to the nations, not a source of darkness by returning to a practice once deemed honorable but now perceived by the global masses as barbaric. The Jewish people have transitioned in our own existential consciousness and our spiritual relationship to our animal’s slaughter has been altered irrevocably.

There is no question that the notion of animal sacrifice seems bizarre and inexplicable to us. Indeed, as the author suggests, offering sacrifices seems to modern man barbaric, archaic and brutal. However, it seems to me the discomfort we have with offering sacrifices is not so much an expression of moral opposition or protest, but rather a direct result of our unfamiliarity and inexperience with them.

Why do I say that? Because we bind ourselves with animal parts every morning when we don our tefillin, we kiss animal skin hanging from our doorposts when we reach for our mezuzas, and we have regular public readings from our Torah scrolls made of animal skin and tied together with animal sinews and veins, all of which we feel is normal and mainstream. Observant Jews recognize these mitzvos as non-negotiables: obligations that are incumbent upon us. Though we may find them strange or peculiar, our devotion to them leads us to study their symbolism, meaning, and purpose and thereby to seek inspiration and fulfillment through their mandated performance.

Animal sacrifices seem strange or even offensive because we have never performed them or even observed them. For the last two thousand years, since the destruction of the second Temple, not only are we not commanded in sacrifices, but we are prohibited from offering them.

While we don’t offer actual sacrifices today, our prophets ensured that their theme and purpose would not be forgotten or neglected in the absence of the Beis Ha’Mikdash. "U’neshalma parim sefaseinu,” said the prophet Hoshea (14:3). “And let our lips replace the (sacrificial) bulls.” The Midrash (Shir HaShirim Rabbah 4:3) teaches that when we are precluded from offering physical sacrifices, Hashem considers our recitation of the sections that describe them as a substitute. Though, sadly, few are there in time or pay it the proper attention, in fulfillment of the prophet’s charge, our davening each and every day begins with a reading of the korbanos.

Why do korbanos play such a central role, even today, when we can only speak of them, in achieving atonement, personal growth, and closeness to Hashem? In his commentary on the Siddur, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch offers a magnificent insight into the symbolism and purpose of korbanos. We offer animals not as an act of barbarism or to satisfy carnivorous cravings. Rather, says Rav Hirsch, we purchase an animal, bring it to the Temple, and have it sacrificed, to make the statement to the Almighty and to ourselves that we are eager and willing to sacrifice the animal inside us.

In Jewish thought, man lives in two dimensions simultaneously. On the one hand, the Talmud observes, we are members of the animal kingdom who share in common the three basic physical activities of animals: eating, elimination, and reproduction. On the other hand, we have been endowed with a tzelem Elokim, a Godly soul, providing us the capacity to be disciplined, exhibit self-control, and reign sovereign over our instincts and impulses. Life is a perpetual battle between our animal urges that draw us to worldly pleasures and our Godly soul that yearns for higher purpose and satisfaction. A korban, ritual animal slaughter, is a pledge to suppress and control the animal in us and do more to have our tzelem Elokim triumph in its battle.

Rav Hirsch continues by explaining that the practice of sprinkling the blood of the sacrifice corresponds with our commitment to direct our passions to Hashem. The burning of the fats represents our efforts to eliminate gratuitous indulgences. The offering of soles (flour) and shemen (oil) remind us that all our sustenance and wealth are granted only with the consent of the Divine, and therefore must be directed to Him in the form of an allegiance-gift (mincha).

Herein lies the great irony in the controversial blog post. The author essentially argues that we have progressed, become more advanced, sophisticated, and cultured, and therefore sacrifices are not only irrelevant to us but they should be repulsive to us. In light of Rav Hirsch’s insights, I would suggest the exact opposite. Yes, we have progressed in so many meaningful ways.

However, in the area of the battle between the animal and the Godly soul, the temptations of the physical world versus the quest for spirituality, we not only have not progressed, but a survey of advertisements, websites, themes of movies and TV, and behavior of politicians and celebrities shows that we have regressed. The world of marketing seeks to exploit the animal impulse inside us all with messages like “Obey your thirst” and “Just do it.” Look at the infidelity rates and the obesity statistics and you cannot help but conclude that for many modern people, the animal instinct is defeating the Godly, disciplined soul.

And it is not just in the “outside” world that the battle is being lost. Within our own community and if we are to be honest, within ourselves, the battle is raging and victory for the tzelem Elokim is far from a foregone conclusion. Challenges with ostentatiousness, excess, modesty in all forms, food indulgence, unhealthy competitiveness and the race to keep up with others is evidence that while we the Orthodox community have made progress in so many remarkable ways, we too have regressed when it comes to the pursuit of the piety that results in the defeat of the animal instinct to the will of the Godly spirit.

The message and symbolism of animal sacrifices are in fact more relevant than ever for our generation and our culture, not less. Our prayers and pleas should not be in protest of a third Temple or in opposition to the notion of sacrifices but in desperation for them and their assistance in helping us realize our potential as Godly souls over our endless animal temptations.

My prayer is not that God nullify sacrifices, but that we, His people, renew our efforts to study them, to recite them with deep kavannah (intent), and to find in them the strength to begin each day with a pledge to slaughter the animal inside us so that all of our behavior and actions be at the direction solely of our sacred tzelem Elokim.